Choice-Supportive Bias Gives False Confidence to Your Hiring Decisions

By Wendy Beach, VP of Talent Science Solutions at Stang Decision Systems

Spoiler alert: here comes some real-life science to distract you from the daily news! In all seriousness…there is beauty, I’ve found, in the science behind what helps our company match people to jobs and jobs to people.

Because it’s good to understand why we do things a bit differently, this blog on choice-supportive bias is our first in a series of discussing the relevant cognitive biases which prevent many people from making good hiring decisions.

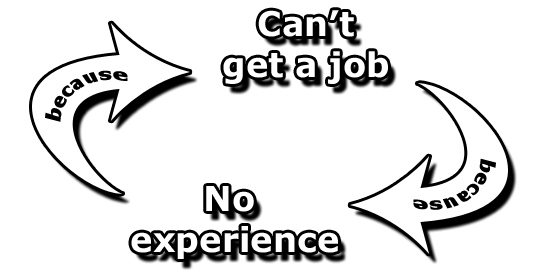

Once we make a choice, we have the tendency to support that choice (dig in our heels, close our minds, stick our heads in the sand…insert your favorite saying here) even if it doesn’t make sense in the face of new information. Industrial psychologists call this choice-supportive bias, and it is one of many cognitive biases that affect our decisions.

I would argue that choice-supportive bias has become even more significant as our world has become more competitive and information leading to constant decisions is available at an ever-increasing pace.

What!? Isn’t it a contradiction to say that in an increasingly fast-paced and competitive business world the “status quo” is becoming even more ingrained in our personal and professional lives? I’d argue we are living in a world of “revolving status quo.” In other words, we try even harder to maintain normalcy and consistency in certain parts of our lives because other parts are changing so quickly.

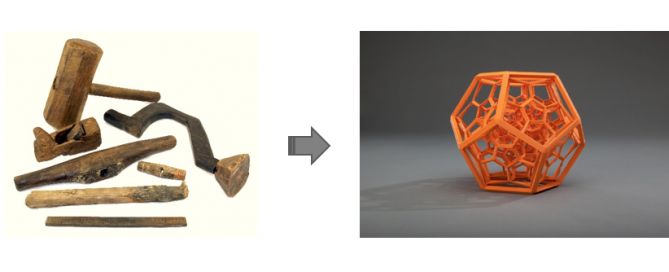

The two main reasons for this are: (1) the increase in disruption via information and technology available at any moment; and (2) choice-supportive bias. The information and technology pushes us to change, and choice-supportive bias pushes us to lock in previous choices. The conflict between the two leads to pockets of rapid change and pockets of locked-in behavior. Oddly, this implies that rapid change in many areas of business run parallel to systems that may be archaic or obsolete.

Anyone in business, from manufacturing to service, has every moment of the day filled with constant choices and decisions. Since our company is focused on talent, I’m going to simplify this conversation (whew!) and emphasize the importance of resisting choice-supportive bias when attracting, retaining and developing talent. Specifically, I’m going to use the resume as a shining example of how cognitive biases can ultimately reduce decision accuracy.

“Eyeball to eyeball and a handshake.” Does anyone else feel a bit of nostalgia for the times when this was the way you decided if a person was a good fit for your team? In the 1940’s, believe it or not, the resume was a new trend, and it typically included weight, age, height, marital status, and religion (not very PC!). It became popular as companies grew and roles became more skilled or specialized. Resumes also helped as workers had more types of work experience and more geographic mobility. For a time, this was an improvement that made a lot of sense.

The reality of today, however, is quite different. In this fast-paced world, most people do not want to spend hours crafting the perfect resume. What if a good candidate simply doesn’t use the right keywords, or has a job title or education that doesn’t describe his or her full skill set? What if some candidates pay graphic artists and editors to make their resumes shine in a way that others never will?

From the perspective of the hiring manager, who wants (or has time) to spend hours sorting through hundreds of resumes–or worse–resumes with cover letters? Hiring managers and human resources staff are often faced with mountains of paper and/or electronic documents in varying formats, fonts, and length. Nonetheless, thanks in part to choice-supportive bias, the resume has become the default tool for evaluating candidates. Resume, cover letter, status quo, check.

When a “new” idea came along in the not-too-distant past to allow technology to help us with the tedious task of going through resumes, we didn’t start from scratch and look at what computers and data could truly do to elevate the process. Instead we, as a society, collectively held on to the “status quo” while adding an electronic layer. Our “choice-supportive bias” resume protocol was still intact, and the document was simply stored on a computer.

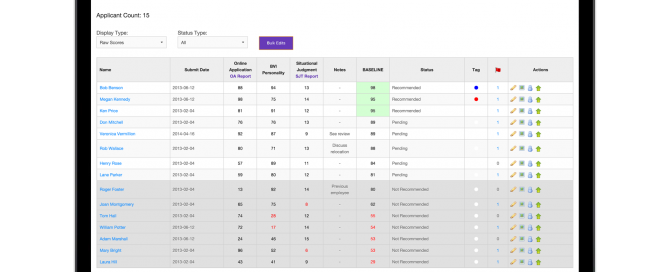

Resume parsing, keyword searching, arbitrary cut-offs of grade point averages…those were all born of using a computer to get through big stacks of documents faster. Did that increase our odds of a great fit? Actually, even though electronic applicant systems were perceived to increase efficiency, they quickly become talent pool limiters, and often increase inefficiencies when it comes to finding the most suitable candidates for a job. There are many internet forums that focus on how much candidates hate applicant tracking systems, and internal human resources staff tend to agree.

What if we used computers and data to help us get to know people better as a first step in a hiring process, not simply weed them out? Can computers really help us be MORE human?

You’ve probably guessed by now that using technology to make the hiring process more accurate and more “human” is our focus at Stang Decision Systems. Our clients are bypassing resumes altogether and working with new ways to see their candidates as a complete person. Curious how? We’d be happy to show you.

When the resume step is eliminated, we start to wonder why we held on to it for so long. Could it be that we’re simply human, with some pesky choice-supportive bias? I think so, but I’d love to hear other theories.

As with any limiting quality, we should not expect to be other than human, or beat ourselves up over it. What we can do, as intelligent decision makers, is become more aware of our biases and search for ways to overcome them. The human brain has a wonderful autopilot mode, but when decisions are truly important, we need to take the wheel and steer toward better options. That is truly progress beyond the status quo!